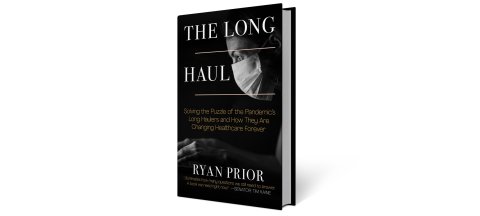

Rounding on three years into the coronavirus pandemic, scientists project there are over 100 million COVID long haulers worldwide. A recent Brookings Institution study estimated that around 16 million working-age Americans currently have Long COVID, costing $168 billion a year in lost earnings, not to mention the missed personal and professional opportunities and the high toll it takes on families. And countless more will suffer from it before the pandemic is in our collective rearview mirror. Post-viral illnesses, like chronic fatigue syndrome among others, are not new, but in the wake of Long COVID, how they are analyzed and treated is groundbreaking. The patient-led medicine that has come to the fore to seek answers will have long-lasting ripple effects on the medical establishment and on how post-viral illnesses are diagnosed and treated. It is to this topic that former CNN reporter Ryan Prior turns in his new book. Prior, a long-time chronic fatigue syndrome patient, who also suffered from Long COVID, focuses on long haulers and the patient-centered groups that sprung up around it in The Long Haul: Solving the Puzzle of the Pandemic's Long Haulers and How They Are Changing Healthcare Forever (Post Hill Press). In this excerpt, Prior shares how as he was covering the pandemic as a journalist, it became increasingly clear that the tragedies of COVID complications would likely be one of the greatest scientific opportunities of the modern era, helping us understand myriad post-viral illnesses which would, in turn, help millions of people for years to come.

It isn't just life or death. Even a mild case of the virus can disable many of us for the rest of our lives. And our leaders had no idea. That thought hung in the back of my mind on the last day of February 2020, while I was working a weekend shift filling in as a breaking news writer for CNN's Ticker, drafting updates on global events that scrolled across the bottom of millions of viewers' screens. From the video feed at my desk in the main newsroom of CNN's world headquarters in Atlanta, I watched as Vice President Mike Pence stepped to the podium in the White House briefing room to give an update on that morning's meeting of the White House Coronavirus Task Force. After his opening statement, Pence introduced Alex Azar, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, who sought to assure the public that the administration had the outbreak under control.

"It's important to remember," Azar said, "for the vast majority of individuals who contract the novel coronavirus, they will experience mild to moderate symptoms, and their treatment will be to remain at home, treating their symptoms the way they would a severe cold or the flu."

His stable demeanor and cool command of the room belied more stubborn truths brewing behind what we now know was an emergent global pandemic. For my own part, I dwelled on something much different from what most people were concerned with as I took in Azar's words: I was 30 years old at the time. At first glance, I might have looked like one of the strong young people we imagined with immune cells that could easily stare down the crown-shaped virus circulating the globe. But like seven million others in the U.S., I was immunocompromised.

I knew that if I were infected with the coronavirus, it could mean much more than two weeks of illness at home. Although it might not kill me, it might threaten every ambition I held for my professional career and every dream of one day being a husband and a father.

On March 11, 2020, I was shadowing a producer on the Anderson Cooper 360° show. During the eight-hour shift, the producer frequently used sanitizing wipes to clean every inch of the workstation in our small edit bay. The day was spent preparing for President Donald Trump's address from the Oval Office. Much of the speech was an attempt to project a Reaganesque optimism, broadcasting the idea the virus was no match for the greatest nation on earth.

Later that night as I walked out of the CNN Center, a building to which I'd reported nearly every day for five years, I didn't realize that as the whole company shifted to working from home, it would be 17 months before I set foot in the office again.

A week later, I began what would become a year-long assignment as a features writer for CNN primarily focused on science, health and wellness. As with nearly everyone on earth, just about every conversation I would have over the next year revolved around the virus. I couldn't and can't espouse expertise on all of the minutiae of immunology and epidemiology, but there is one area where I do consider myself an expert: I have lived with a long-term illness following an infection for more than 15 years. And since the start of the pandemic, I have told the stories of those with similar experiences due to COVID-19.

On the night of his Oval Office address, Trump focused his comments toward "the vast majority of Americans," explaining that "the risk is very, very low. Young and healthy people can expect to recover fully and quickly if they should get the virus." I knew those words to be inadequate then. And over the ensuing months, I would continually publish stories reporting on a growing group of survivors who would come to be called COVID-19 "long haulers."

It would turn out to be true that the majority of patients infected with the virus would get better quickly, but that number would fall short of being the vast majority. Public health leaders' early comments about most people getting better, which reflected the prevailing public belief at the time, didn't begin to capture the full picture of the disaster that would happen in the lives of many of the pandemic's survivors.

In the weeks after lockdowns began, I received a disquieting message from Linda Tannenbaum, executive director of the Open Medicine Foundation, a nonprofit organization in California dedicated to funding research for complex chronic diseases. She'd been a friend and a source for my stories for nearly a decade. The scientists her organization worked with were prestigious forward thinkers, and she was alarmed at what they could already see. She confided that she expected the novel coronavirus, which had been designated SARS-CoV-2, could cause years or even decades of disability in some sufferers. So many other long-time sources reached out with the same warning that I began to dread picking up my phone.

COVID-19 had its predecessor in the first severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) virus, which mainly terrorized Asia in the early years of the new millennium. For many patients, Tannenbaum explained, that virus had left years of wreckage in its wake. A 2009 study of 369 SARS survivors published in JAMA Internal Medicine showed that four years after initial infection, some 40 percent had a chronic fatigue problem, and 27 percent met the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's diagnostic criteria for chronic fatigue syndrome. If the second SARS virus—which causes COVID-19—were to prove as wicked in the long term as the first, it might mean years of disability for a swath of humanity.

And looking at scientific literature about previous epidemics, I saw similar trends in history. Before researcher Jonas Salk pioneered a vaccine in the 1950s that led to the disease being virtually eradicated, the polio virus fueled terrifying outbreaks around the world for millennia, accounting for many deaths among children and causing irreversible paralysis in about one in 200 patients. But, less commonly acknowledged, the virus also caused post-polio syndrome in 25 to 40 percent of survivors, leading to muscle aches and fatigue that could last for decades.

Likewise, the Ebola virus, which caused more than 28,000 cases during its 2014–2016 epidemic, left its own post-viral syndrome. During that outbreak, Ebola killed more than a third of those it infected, and more than 70 percent of survivors were left with a constellation of symptoms including headaches, joint pain, fatigue and menstrual cessation.

In 2020, as health care systems around the world were overwhelmed with dying patients, thousands of very sick people dealing with the ongoing effects of COVID-19 began gathering in online support groups offering each other guidance as months passed and their expected recovery never came.

In July, the CDC released a study of 292 COVID-19 patients showing that 35 percent of them still had symptoms after two or three weeks; among younger people between ages 18 and 34, about one in five included in the study had not fully recovered. Assuming that data generalized to the wider population, it was evidence showing that COVID-19 could linger beyond its two-week recovery time and long-term symptoms were a possibility.

The next month, a science writer colleague sent me a study from the United Kingdom that burned itself into my consciousness. It appeared to show that about three-quarters of those hospitalized for COVID-19 experienced symptoms beyond the 12-week mark. Another long hauler symptom study out of the U.K., which has now tracked five million patients via a symptom-tracking app, showed that one in 10 people were sick for at least three weeks.

The fears that my sources and friends had expressed to me were being realized.

But hope—seemingly irrational at the time—hung at the edge of each of these conversations.

It was becoming clear that studying why some people get sick, and stay sick, could be one of the greatest scientific opportunities of our lifetime.

We are now in the midst of a polio-like epidemic of long-term disability. Within the first two years of the pandemic, scientists projected there were up to 100 million long haulers worldwide. Many of them experience cognitive illness that resembles brain injury, which leaves the possibility of a later epidemic of neurodegenerative diseases such as dementia and Parkinson's years down the road.

Working together, it's possible to define, treat and defeat Long COVID. And in the process, we might be able to end the years of misunderstanding endured by those with diseases such as chronic Lyme, myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME/CFS, formerly known as chronic fatigue syndrome), Gulf War syndrome, fibromyalgia, multiple chemical sensitivities or postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. As with Long COVID, the underlying pathology of each of these diseases is hard to detect, the scientific base isn't well developed and patients are often told their symptoms are all in their head. COVID-19 is a once-in-a-century pandemic, but it's also a once-in-a-century opportunity to leverage public awareness and political capital into finally building a true understanding of post-viral and autoimmune illness.

More than 150 million Americans, or about 40 percent of us, have a chronic disease. I've claimed my own form of citizenship in that tribe for more than a decade. Millions of Americans will join this group as a result of their COVID complications. One of the most important questions long haulers can ask the world is whether COVID-19 complications are random or whether they strike particularly acutely in patients with particular environmental, genetic or epigenetic profiles.

COVID-19 long haulers are like canaries in a coal mine, people whose experiences we can peel back to reveal important insights about our immune systems, our medical system and our common humanity.

Adapted from The Long Haul, published by Post Hill Press. Copyright © 2022 by Ryan Prior.